Caring for carers: survey data reveal the needs of those who look after patients with severe mental illness

Some would say it has been a long time coming. But the practical and emotional needs of those who care for people with mental illness are now being given the attention they deserve. Reflecting this new emphasis on inclusion, the first symposium of the entire ECNP conference was on the role of carers, and how better to support them.

Carers are in the patient’s world, which is where recovery happens. The need is for a paradigm shift so that family carers are treated as the vital resource that they are, and as partners in promoting patient recovery.

Historically, psychiatry has sometimes had a difficult relationship with the families of those with mental illness, session co-chair Professor Shitij Kapur (King’s College, London, UK) reminded the meeting. But we should be working together with family carers to improve the lives of sufferers, he urged. This carer-focused meeting marks a new departure for ECNP and something it will increasingly be doing.

Another welcome initiative is that we now have survey-based evidence, rather than anecdote, about how carers think and feel. Chantal Van Audenove (University of Leuven, Belgium) presented data from the Caring for Carers (C4C) survey, the first international study of its kind, conducted in 2014.

The sample was drawn from carers in 22 European countries who have contact with national organisations that are members of EUFAMI (the European Federation of Associations of Families of People with Mental Illness). Of the 1111 carers who completed the anonymous questionnaire, 80% were women, with a mean age of 58 years. They were caring for a son or daughter in 76% of cases, and in 64% of cases the person cared for had schizophrenia.

On average, respondents cared for their loved one for 22 hours a week and had been a carer for the previous 15 years. Half had never been able to take a break. So it is perhaps not surprising that 38% of respondents said they felt unable to cope with the constant anxiety. And 33% said their role as carer worsened their physical health. Almost half were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with their ability to influence the medical management of their loved one.

Yet there were some positive points: 70% said the experience of caring had made them more understanding of others’ problems; and 54% that they had discovered inner strength.

That said, 93% would like additional support. And this includes additional information.

New on-line resource for carers

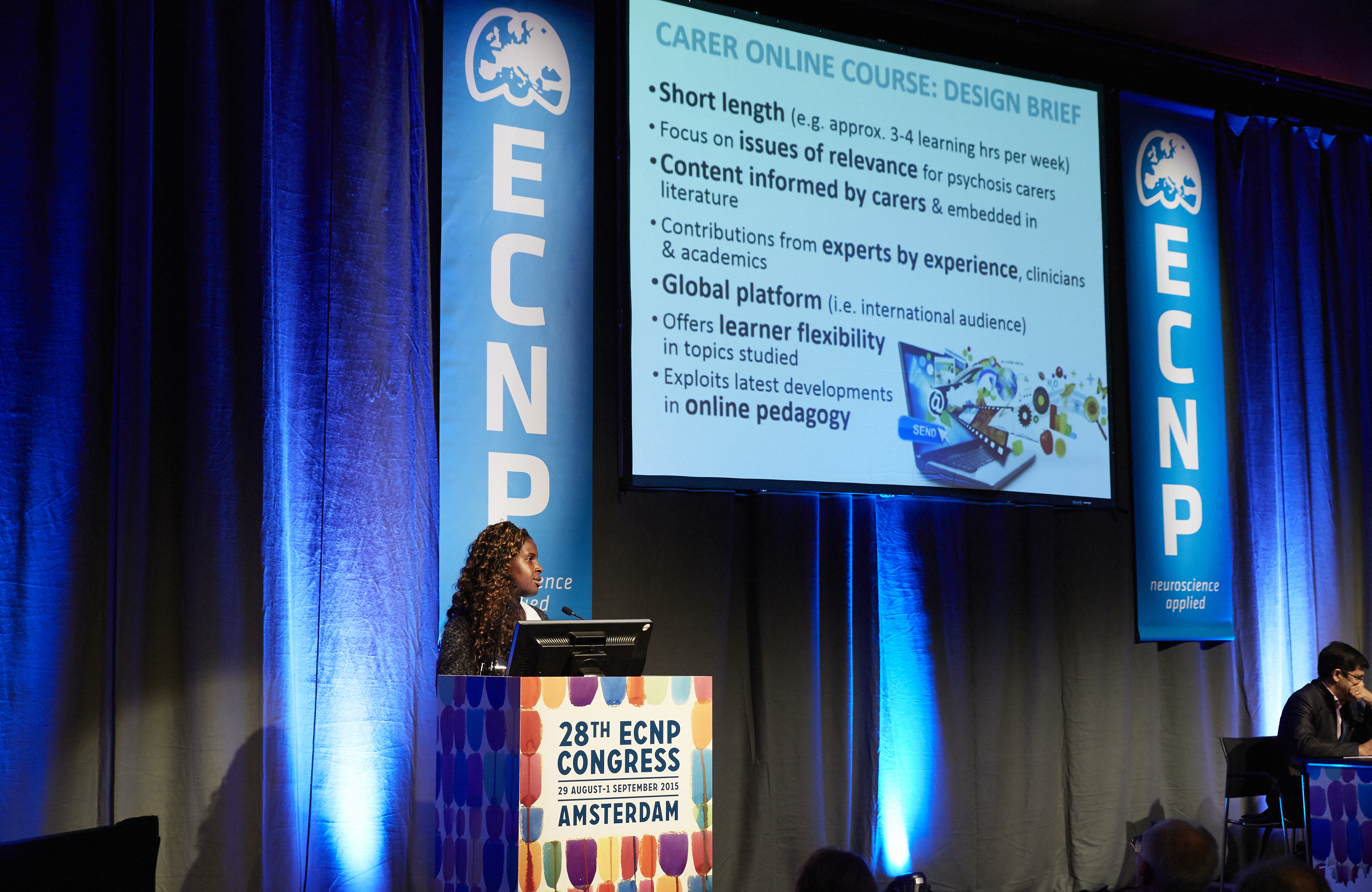

No sooner had this need been identified than the first on-line educational tool of its kind was in development. Dr Juliana Onwumere (Kings’ College, London, UK) gave an overview of the Caring for People with Psychosis and Schizophrenia programme. The free course, which aims to have a global reach, will run for the first time in October 2015. It involves the carer in study lasting 3-4 hours per week for two weeks. The multidisciplinary interactive content, which has been informed by carers themselves, covers topics such as psychological treatments, medication, recovery, dealing with difficult behaviour and how caring can affect the wellbeing of the carer.

Across Europe, millions of family members juggle the demands of caring for a loved one with mental illness and the need to meet their own goals in life. Health systems are saved millions, but often at great cost to the carer in terms of social isolation and limited career prospects. With the shift towards managing patients in the community, the role of the family carer has never been more important. This should be fully acknowledged not only by health care professionals but by policy makers and society as a whole.

Our correspondent’s highlights from the symposium are meant as a fair representation of the scientific content presented. The views and opinions expressed on this page do not necessarily reflect those of Otsuka and Lundbeck.